By Jennifer Casa-Todd

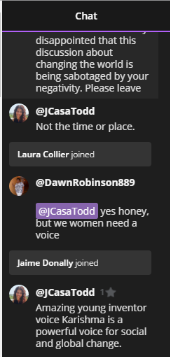

It seems that everywhere I turn on social media or the news lately, there is yet another instance of hate resulting in the loss of life. By the same token, I belong to a Voxer group made up of so many races and religions that it truly allows for multiple perspectives and courageous conversations when a current event occurs or a discussion topic is brought up. Just listening to everyone talk about their own experiences has helped me to grow in my understanding of the complexity of it all. My buddy, Justin Schleider said it best when he said that we are forever changed as a result of our group, because we notice inequality more frequently as a result of having participated in these discussions and having our ideas pushed and challenged.

Throughout our discussions, I always bring it back to the classroom. How do we address important issues of inequality and injustice with other teachers and students? Do we? How do we help students to see alternative perspectives in the media? Can social media be a vehicle for social action and change?

Slacktivism

Some would answer no. The term “slacktivism,” which is made up of a combination of the words “slacker” and “activism,” has increasingly been used to describe the disconnect between awareness and action through the use of social media (Glen, 2015).

Slacktivism can be defined as “a willingness to perform a relatively costless, token display of support for a social cause, with an accompanying lack of willingness to devote significant effort to enact meaningful change” (Kristofferson et al., 2014) and thus has a negative connotation.

And yet, isn’t awareness a goal of education? If a young person learns about deforestation, reads about organizations doing something about it, and “likes” their page, or demonstrates a positive response, isn’t that exactly what we want? Might that eventually lead to a more active stance as the child grows older?

I think of the Ice Bucket Challenge craze of last year as an example of how awareness can be spread through something going viral on the internet. If you don’t remember, the movement required that you video-tape yourself throwing ice water over yourself & challenging others to do so as well. You were also supposed to donate to ALS (Lou Gherig’s disease). At the time, it was criticized because many people were just interested in the fun of the challenge. This is in line with typical criticism of slacktivism which it that it is more about “‘feel-good back patting’ through watching or ‘liking’ commentary of social issues without any action.” and the fact that oftentimes there is minimal time and effort, without mobilization and/or demonstrable effect in solving a social issue (Glen, 2015). And yet, there is no way that people would have had known about the disease without this movement becoming popular on social media. Just recently, there was a breakthrough in ALS as a result of the money raised during that craze. So slacktivism, despite its negative connotation can actually be positive.

Much has been written also about the Kony movement of 2012 (Jenkins, et al, 2015) (Glen, 2015) as an example of social activism on the internet. I remember this campaign vividly because at the time, a friend of the family, who is a non-reader, not interested in school, and generally apathetic when it comes to any sort of causes became very interested in learning about Kony and child soldiers. I directed her to sources and she voraciously read them to learn about the cause. We often talk about students not coming into our classes with prior knowledge, but I wonder whether or not if we meet them where they are and bring in cultural references from social media, that we might have greater success helping them to build an understanding of politics and culture.

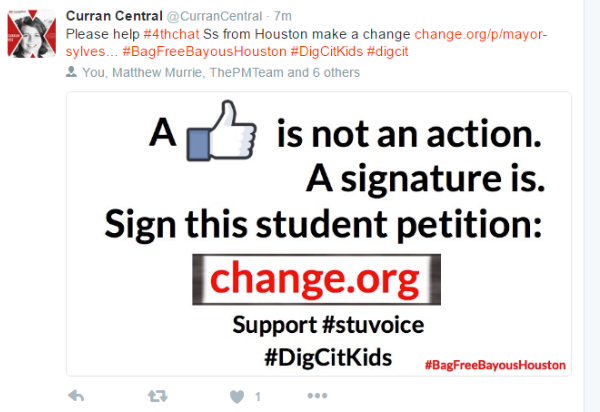

I love this tweet by Curran Dee (a mother/son account) which really does emphasize the difference between activism & slacktivism:

Citizenship Education

I really appreciate this framework for Citizenship Education in the new revised Canadian World Studies (and other revised Ontario Curriculum) as it reminds us that active participation in society are a necessary end goal. Today, this means that technology and social media can help students develop a voice and become actively involved in causes about which they are passionate. But it also suggests that teaching citizenship is an important goal to the development of the whole child.

Connecting Classrooms

When we provide students the opportunity to learn about other cultures in the world, by connecting our classrooms, we are helping them to see other races and cultures as human beings. This can only be a good thing. This can ideally be accomplished via technology and/or social media. Students, can for example engage in a Google Hangout or a Blab with other classes to discuss an issue. They can engage in a Twitter exchange. I have heard so many powerful stories and have personally experienced transformation of student points’ of view as a result of virtually meeting kids from other countries or communities. In one case, where one of our local schools connected with Julie Balen’s class, our students admitted that they really had no idea that the students of FNMI backgrounds were “16 year olds just like us”, and a student from Wikwemikong school admitted to thinking that everyone outside of her reserve was white and that she was surprised to see the class had so many “colours”. One of my friends, Shervette Miller-Peyton spoke about how interesting it was for her class to connect with a class from Brazil because they had made so many assumptions about what students outside of the States would be like. They were shocked to hear that the students knew about their own culture. Connecting students allows them to really get to

Multiple perspectives

I would suggest a four-pronged approach to any issue so as to minimize bias and radical responses BEFORE they actually go online. Something like this which would obviously need to be modified based on the grade:

| I am ___________and from my perspective…: Respond as the perpetrator’s son (daugher, sister, brother, mother) |

I am ______________and this my perspective… Respond as the perpetrator’s victim’s (daugher, sister, brother, mother) |

| I am ___________and this my perspective: Respond as a community leader |

I am ___________and this my perspective: Respond as a bystander |

| Reflect: I used to think, and now I think…

|

|

Student Leadership

We have always included opportunities for learning about social justice issues in the classroom. Today, we are able to empower our students to use their own voices to advocate for change. These are just kids leveraging social media and technology to spread good in the world.

Just this morning, I read about Two fourth graders who started a plastic bag petition in Houston. It was shared on Twitter by fourth grader, Curran Dee.

Hannah Alper, a 13-year old activist and social-change maker always posts great ideas for how to help. Read her post on how to help support Ronald McDonald Houses.

Joshua Williams, founder of Joshua’s Heart an organization dedicated to feeding the hungry, promotes a positive stance on the issue of gun violence.

Harry Potter Alliance

I learned about the Harry Potter Alliance from the book, Participatory Cultures in a Networked Era. It’s a really interesting resource where social activism and different fandoms (primarily Harry Potter) collide. The website says its goal is to make “activism accessible through the power of story.” The toolkits focus on different issues and provide background as well as concrete ideas of how to build awareness about those issues. It would be a great resource for teachers and students alike.

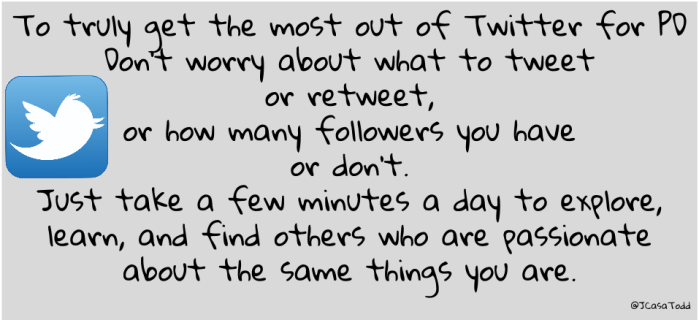

Hashtags

A great way to promote activism in the classroom is to check out the hashtags for current events on Twitter or Instagram and contribute positively. I reflect on the power of hashtags here.

These are a few hashtags shared with me by Alec Couros which he uses in his courses to demonstrate some major online campaigns.

I always check what’s trending on Twitter or Instagram to see if any topical hashtags might be relevant to a unit or theme being studied (or could replace what I had in mind).

Keep it Positive

I would also recommend that you Err on the Side of Positive (Couros, 2016) and beyond that respond with empathy, positivity, openness, sensitivity, and love. Keeping interactions on social media positive will prevent misunderstandings and negativity.

What do you think of taking action using social media?

References:

Couros, G. (2016, June). Err on the Side of Positive. iPadPalooza. June, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zoMn4063yc4

Glenn, C. L. (2015). Activism or “slacktivism?”: Digital media and organizing for social change. Communication Teacher, 29(2), 81-85. doi:10.1080/17404622.2014.1003310

Groetzinger, K. (2015, December 10). Slacktivism is having a powerful real-world impact, new research shows. Retrieved July 31, 2016, from http://qz.com/570009/slacktivism-is-having-a-powerful-real-world-impact-new-research-shows/

Kristofferson, K., White, K., & Peloza, J. (2014). The nature of slacktivism: How the social observability of an initial act of token support affects subsequent prosocial action.Journal of Consumer Research, 40(6), 1149-1166. doi:10.1086/674137

Robinson, Matthew (2016) Department of Government and Justice Studies. Appalachian State University. Retrieved July 31, 2016, from http://gjs.appstate.edu/social-justice-and-human-rights/what-social-justice

Vanwynsberghe, Hadewijch, and Pieter Verdegem. “Integrating social media in education.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 15.3 (2013). Academic OneFile